I. Origins of the Dialectic of Modernity

Bourgeois vs. Bohemian

There is much scholarly debate on precisely when the Age of Enlightenment began. Fortunately, I am not a scholar. Therefore, I will make the entirely capricious claim that it was when the ideas of John Locke were transmitted from England to France by François-Marie Arouet, better known today by his nom de plume—Voltaire.

For two and a half years, Voltaire had been in exile across the Channel to escape the fallout of an aborted duel with a young nobleman. In 1728, when finally permitted to return, he came bearing gifts for his forsaken homeland: an assortment of radical ideas about the comparative virtues of the two nations. These thoughts would became a collection of essays, Letters on England, praising its constitutional system, religious tolerance, and advances in science and art, while condemning France’s absolute monarchy, Catholicism, and intellectual indigence. The book, unsurprisingly, was banned by the authorities and publicly burned—requiring him to once again flee Paris. But it was already too late.

Letters from England became one of the most important literary events of the century and helped spread liberal thought across the continent. For the next seventeen years, Locke’s revolutionary doctrines of life, liberty, and the pursuit of property dominated Paris’ intellectual salons—that is, until a little-known, socially awkward autodidact published a brief, but devastating critique of this schema and completely altered the trajectory of world history.

With the publication of his Discourse on the Sciences and Arts in 1750, Jean-Jacques Rousseau split modernity in two (both chronologically and ideologically), laying the foundation for our two political poles today—a clash commemorated in the crypt of Paris’ Pantheon, where the two men were immortalized during the revolution. On the right stands Voltaire; on the left, Rousseau: eternally staring each other down in mutual enmity. This event also gave birth to what I call the “dialectic of modernity.”

At the heart of this struggle was two competing archetypes that embodied the ideas of Locke and Rousseau: the bourgeois and the bohemian, respectively; or put less arcanely, the businessman and the artist. At stake was the question, What is of higher value: comfort and security or adventure and authenticity? For Voltaire and his Enlightenment compatriots, the ideal society that was to replace Europe’s teetering monarchies was the “commercial republic,” built on free inquiry, free enterprise, and free trade. The goal, in their predecessor Francis Bacon’s words, was to “relieve Man’s estate” by unlocking the secrets of nature through science and technology. This could best be achieved, they believed, by elevating human being’s natural desire for self-preservation to the highest social value. Society, from now on, would be primarily centered around discovering the best methods to achieve this end.

Rousseau’s attack on this new vision of society is multifarious and confusing (and possibly confused)—taking political, social, and individual forms that are themselves in tension with one another. These shall all be explored in subsequent posts; but for our present purposes, the last on this list is most salient, and best reveals where we find ourselves in the Dialectic of Modernity.

The doctrines of Locke and Voltaire had sought to radically change the relationship of the individual to society. No longer was the health of the whole to be the goal, but the freedom of each person to pursue their own private goals. Rousseau sums up the results of this change in orientation with the term “bourgeois,” which he expounds upon in his novelistic educational treatise, Emile:

Always in contradiction with himself, always floating between his inclinations and his duties, [the modern individual] will never be either man or citizen. He will be good neither for himself nor for others. He will be one of those men of our day: an Englishmen, a Frenchman, a bourgeois. He will be nothing.

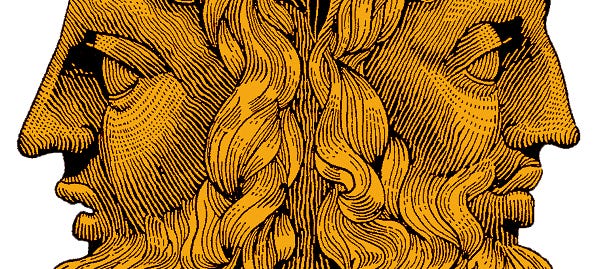

The main issue Rousseau has with this new sort of human is that they are Janus-faced. Torn between the demands of social duty and their desire for self-interested self-preservation, they are unable to be either authentic to themselves or to their community. They need others in order to achieve their ends, but they must always pretend to be something they’re not in order get there.

In opposition to the commercial individualism advocated by Locke and Voltaire, Rousseau puts forth an image of artistic individualism, i.e. bohemianism. This was a product both of his autobiographical writings—The Confessions and Reveries of the Solitary Walker—and his life. In addition to being a world-historical philosopher, Rousseau was also a highly successful creator: poet, composer, novelist, playwright; inventor of an unorthodox musical notation and author of a musical dictionary. His opera The Village Soothsayer was performed before the king at Versailles, and his epistolary novel Julie; or, The New Heloise was so popular publishers could not keep up with demand and had to rent it out by the hour.

The essence of this alternative vision of life is summed up in the first few sentences of his Confessions:

I wish to show my fellows a man in all the truth of nature; this man will be myself. Myself alone. I feel my heart and I know man. I am not made like any of the ones I have seen; I dare to believe that I am not made like any that exist. If I am worth no more, at least I am different.

Whereas for the bourgeois, life is centered around self-preservation, for the bohemian, it is all about self-expression.

The battle between these two antithetical ways of life for the soul of Western civilization was the animating force of history for more than 200 years. It could even be said that the political disputes between liberalism, communism, and fascism were driven by this exact same concern, and that Marx’s denunciation of the economic bourgeoisie was ultimately a concern over the inauthentic individuality embodied by this class (see his early humanistic writings, The German Ideology and The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844).

Yet, this struggle between the bourgeois and bohemian does not seem to concern us at all today. Something momentous then must have occurred, where this distinction no longer has purchase. Instead, we have all become entrepreneurs of the self, and individuality has been transmogrified into the “personal brand.” Artistic authenticity has been exchanged for virality. The Dialectic of Modernity appears to have come to an end. In my next post, I will explore how this new situation came to be.