“You can drive nature out with a pitchfork, she will nevertheless come back.”

— Horace, EpistlesWhen revolution broke out in North America in 1776, Parisians burst into joy and exaltation—at least those of the Lumières persuasion. Hopeful radicals viewed the uprising as a sweeping away of the past’s burdens by a simple people living in close contact with nature: a shining beacon to light the path back from the corruptions of civilized decadence, hierarchy, and established religion. Which is to say, they interpreted it entirely though the lens of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (or at least a certain interpretation of Rousseau). Yet a decade later, when the revolution was codified in the US Constitution, they were scandalized by our conservatism. How could we continue to cling to such relics of the benighted past as checks and balances, a bicameral legislator, common law, and property-based voting rights? These Frenchman, though, were the first of a long line of European radicals inspired by the idea of America while misunderstanding its reality.

Rousseau has never had much of a direct impact here. As scholar Paul M. Spurlin concludes in Rousseau in America, an exhaustive account of this question, “it is obvious that Rousseau had vogue but not influence in eighteenth-century America.” His ideas (like most continental thought) first began being smuggled in through literature, not philosophy, and by the mid-1790s, Rousseau’s epistolary novel Julie, or the New Heloise was a best-seller, surpassed only by Gulliver’s Travels and Shakespeare. But with the debacle of the French Revolution, his political doctrines became totally anathema. Over the course of the nineteenth century, however, bits and pieces of his thought continued to seep in through the likes of Hawthorne, Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. And then with the mid-twentieth-century cultural revolution, Rousseau finally become a force of nature in America—it is just by that time, no one knew who he was anymore.

In my last post, I explored the origin of the “thesis” of what I call the Dialectic of Modernity: the bourgeois businessman. It is in Rousseau’s conception of nature held by these first counterculturists that we find the antithesis in this equation: the bohemian artist. Whereas the bourgeois sought to conquer nature, the romantic bohemian sought to harmonize with it. Nature should not be mastered through science, technology, and industry, it should be respected as a source of awe. Humans do nothing but corrupt and ruin nature, creating toxic waste and microplastics, GMOs and high fructose corn syrup. Presuming to know nature through our artificial methods and techniques, we thus assume to know better than nature. We shall now examine this alternative view and its consequences.

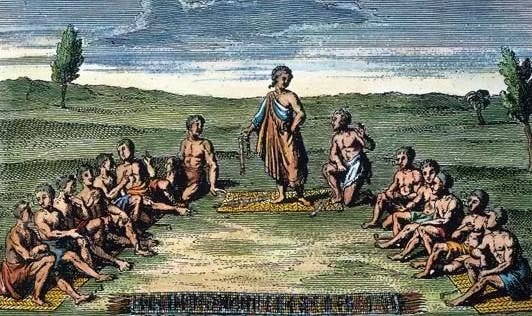

Modernity began, as I have claimed, with the discovery of the New World. Columbus’ revealing of a hitherto unknown territory caused a revolution in our epistemological assumptions: the Unknown became the not-known-yet. And equally important were its social implications. Up until that moment in Europe, monarchy, aristocracy, and feudalism were held to be ordained by Nature or Nature’s God, which were parts in a great chain of being connecting the lowliest mineral on earth to the angels up in heaven. The diverse ways of life of the New World natives, however, disrupted this happy myth. Or I should say, a mythical interpretation of the natives disrupted this myth. And Rousseau, more than anyone, is responsible for this revision.

Rousseau had a preternatural knack for the opening line:

“Man is born free, yet everywhere he is in chains.” — The Social Contract

“I wish to show my fellows a man in all the truth of nature; this man will be myself. Myself alone.” — The Confessions

“Everything is good as it leaves the hands of the Author of things; everything degenerates in the hands of man.” — Emile

From the very start, he immediately sucks you in—both to his works, but more importantly, to his core belief: Nature is good. Although the foundation for questioning European mores had already been laid by Hobbes and Locke’s re-conception of the “state of nature,” it was Rousseau’s version that most turned the tables on this old paradigm.

For Hobbes and Locke, Native Americans were a negative example. Sure the Natives enjoyed a freedom and equality that Europeans could scarcely conceive, but we should not envy them. As Locke rebuffs, “a king of a large and fruitful territory there, feeds, lodges, and is clad worse than a day-labourer in England.” In the Columbian Exchange, only natural rights ought to be imported back, not natural living. For Hobbes and Locke, the advances in the arts and sciences made by civilization were unquestionably good. Only with Rousseau does talk of civilization and its discontents begin.

“I see [natural man] satisfying his hunger under an oak,” Rousseau swoons in his description of the state of nature in his Discourse on Inequality, “quenching his thirst at the first stream, finding his bed at the foot of the same tree that furnished his meal; and therewith his needs are satisfied.” This idyllic image of what would later be dubbed the “noble savage” has come to dominate the Western imagination, and has even penetrated into our universities today under the guise of “Indigenous Knowledge.” It turns Locke’s quip about American kings on its head: Tecumseh didn’t need clothes, he had dignity. By living in the world by his own will and skill, he possessed both a nobility and a self-sufficiency that puts the civilized world of specialized slaves to shame. And it was this image that the Lumieres projected upon America during the Revolution. But with the dual disillusionment caused by our revolutionary conservatism and then the madness of their own revolutionary efforts, Rousseau’s politics was soon displaced by an artistic interpretation—reinforced by Rousseau’s own lifestyle.

What is perhaps most astounding about Rousseau is not only did he write compelling works of philosophy, he was also a highly successful creator: composer, novelist, playwright; inventor of an unorthodox musical notation and author of a musical dictionary. His opera The Village Soothsayer was performed before the king at Versailles, and his novel Julie was so popular, European publishers had to rent it out by the hour. Above all, it was these artistic feats, paired with his own eccentric style and personality, that have defined the essence of the counterculture ever since. Whereas the bourgeois are motivated by the negative proposition of self-preservation, bohemians follow Rousseau’s Solitary Walker in affirming the fundamental “sweetness of existence.”

The bohemian mythos can be traced back to the nomadic fifteenth century Romani people of France, whom early adherents (mistakenly) believed had emigrated there from Bohemia. It first emerged as fact from the ruins of the French Revolution, as disillusioned radicals attempted to salvage what they could of its emancipatory energy. Bohemianism’s animating principle can best be summed up by Schelling’s jeer, Je méprise Locke—“I despise Locke,” or by Flaubert’s directive, “Hatred of the bourgeois is the beginning of all virtue.” What the Parisian dissidents admired most about this perambulating people was their freedom born out of a life at the margins of society. Thus the foremost bohemian pastime has always been epater les bourgeois—“to shock the bourgeois.”

In twentieth century America, this shock and awe took the form of ungroomed, unkempt, uncouth Hippies. While the buzzcut Buzz Aldrin was stepping upon the moon, they were making love like savages under the moonlight. While their parents settled into suburbs, the youth were “on the road” with backpacks, bedrolls, and stash bags pausing only to sing or play on their way to nowhere in particular. Down with mastering nature, down with progress; back to the land, back to the cyclical rhythms of nature—this was their clarion call. Rousseau had finally conquered America, or so it seemed.

In the twenty-first century, something unexpected has come about: the ideas of Locke and Rousseau have synthesized. As David Brooks describes in his 2000 study Bobos in Paradise, “Defying expectations and maybe logic, people today seem to have combined the countercultural 60s and the achieving 80s into one social ethos.” For nearly 200 years these two types—the bohemian and the bourgeois; counterculture and mainstream culture—faced off against one another, battling for the soul of Western civilization. Yet today, this dispute means very little to us. Hi-tech has been harmonized with high country, and getting back to nature is less about the north star than North Face.

The advent of the Bobo (or Bourgeois Bohemian) has brought the Dialectic of Modernity to an end. The primary task of the Millennial generation, I believe, is to ask what comes next? The task of the following generations will be to realize it.

For now—we dance.